What is an “ICO?”

In the world of finance, there are initial product offerings, or IPOs, where shares of a company are sold to institutional investors and usually also retail investors. An IPO is traditionally underwritten by one or multiple investment banks who help facilitate those shares listings on the stock exchange.

However, in the world of cryptocurrencies, there are initial coin offerings or ICOs. Entrepreneurs who are looking to launch a new cryptocurrency coin or DApp, do so through an ICO, but with great risk. Why?

The lack of regulation and formalities associated with it, which makes it very easy for anyone to start an ICO (more on securities law later). In its simplest terms, ICOs are the cryptocurrency equivalents of a crowdsale. In an ICO, investors give the entrepreneur money so they can then go and actually make the currency.

The idea is to remove intermediaries like banks or venture capitalists. Through an ICO, entrepreneurs are able to raise money without having to give up any ownership of the company.

The Whitepaper

Cryptocurrency is considered to be “the wild west” of digital money, where anyone can create anything and ultimately anything can happen, due to the little regulation surrounding it (more on securities law later).

The ICO process begins traditionally with the release of a whitepaper or document that lays out exactly how the project and system work, in addition to a website.

Once out to the public, the whitepaper and/or website will direct people to send the company money (cash, Bitcoin, Ether), and in return, you get a native token of some sort (“nativecoin”), hoping that currency grows into high utilization and circulation, ultimately increasing the demand and value of the currency.

As previously mentioned, the idea is that the real world fiat you are giving to the company in exchange for their newly created (and ultimately initially worthless) currency, becomes valuable one day, otherwise, hey, welcome to the world of ICOs, cryptocurrency, and the floodgates of potentially thousands of worthless projects.

It’s important to note that most whitepapers are completely and utterly worthless and almost laughable. Why? At the end of the day, a whitepaper is just a promise to consumers about a given venture. It’s one thing to learn about theory, concept, or project through a pretty document or an ICO--but it’s another thing entirely to understand the difference between a conceptual theory and an actual, validated business proposition.

Tokens vs. Coins

It is important to distinguish the difference between “tokens” and “coins”, as both terms are often used interchangeably (and inaccurately).

Cryptocurrency coins have value outside of their native environment, allowing for its holder to do buy, sell and trade it as they wish. Cryptocurrency coins refer to ethereum’s Ether, Bitcoin, and Bitcoin Cash

However, a “token” is a representation of something of value in a particular ecosystem. Think of a game card or game coins you would get at an arcade-like Dave & Busters. You can only use the game card and its tokens at a Dave & Busters location--you cannot use that card outside of it.

Same in the world of digital money. These tokens often only have value in that ecosystem and cannot be used for value outside of it. This could represent value, stake, voting rights, among others.

Security Tokens

A crypto token that meets the elements of the Howey Test, is considered to be a security test. This is where individuals often get into trouble, particularly if they don’t understand themselves what they are creating and offering to potential investors.

Since 1946, the U.S. Supreme Court case, SEC v. W.J. Howey Co. (Howey) continues to remain the leading standard in U.S. securities law for determining whether or not a transaction is considered to be an “investment contract” (securities offering) or a “commodity” under the U.S. Securities Act.

For a token to “pass” the Howey Test and be considered a “security”, three elements must be met:

- Was there an investment of money?

- Was there a common enterprise?

- Was there an expectation of profits predominantly from the efforts of others?

In breaking this analysis down, almost always, the first element is met.

The second element, “common enterprise”, courts have looked to factors where the company has in some way, shape, or form encouraged investors to purchase the token, in reliance upon claims that this particular project would result in an increase in the coins’ value.

As for the final element of the test, Courts will also look to persuasive authority such as company press releases and FAQ’s, to see how the company has publicly held itself out to potential investors, which could reasonably lead one to believe that profits were to be expected.

For more analysis, please read the ATB Coin SEC lawsuit that was first covered by CoinTelegraph, which helped set legal precedent in New York for courts hearing cryptocurrency cases involving potential SEC violations.

Utility Tokens

Utility tokens, on the other hand, are those tokens that don’t meet the elements of the Howey test. These are simply tokens that provide users with a product and/or service. Specifically, holders of these tokens have a right to use the network/platform as well as voting rights.

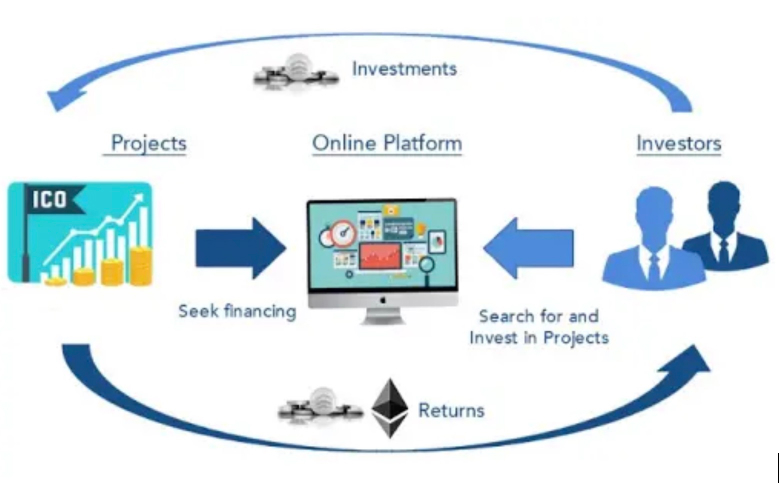

How An ICO Works

Source: Applicature

After the whitepaper is released, the funding stage for the project begins. This is where the developer issues a limited number of tokens (could be utility or security) which establishes a goal for the ICO as well as determining whether there is a demand. If you are looking to participate in an ICO, you traditionally would send funds to the crowdsale address, to which you will receive the equivalent amount in the platform’s native tokens to your wallet.

The Legalities

Up and until December 2017, ICOs were not “officially” regulated. Once the SEC classified tokens from ICOs as “securities” under the Howey Test, the industry watched as many endeavors failed, were fined, and/or ultimately sued in court.

Under the Howey Test, an ICO and its tokens are subject to federal securities law if the token offering represented:

- (1) an investment of money

- (2) in a common enterprise

- (3) with a reasonable expectation of profits

- (4) to be derived from the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.

SEC Cases to Know About

The Legalities

If there’s any SEC case to know about involving ICOs, it’s the one involving KIK, which finally settled at the end of September 2020, after six long months of hiatus.

Kik, a Canadian company with a messenger app of the same name, created a native token (“Kin”) as a way of monetizing its messaging app platform.

Kik sold $50 million in Kin tokens from June to September of 2017 as part of a private pre-sale to 50 investors. As part of the “Simple Agreement for Future Tokens” or SAFT, investors knew they were getting a discount and were in agreement they were purchasing a security.

Later in September, Kik held a public sale of the Kin token, which brought in an additional $49.2 million. The problem was that when Kin was first announced, the SEC hadn’t get created rules for governing crypto, which came out in July 2017.

In June 2019, two years following Kik’s announcement of Kin, the SEC charged Kik with violating Section 5 of the U.S. Securities Act, alleging that Kik had offered and sold securities in the U.S. without being registered. The entire case was based upon whether Kik’s token met the Howey Test.

It’s important to note that both Kik and the SEC agree as to the first element of Howey being met, as money had been invested. However, Kik argued against the other two elements, that there was no common enterprise that could lead to the expectation of profits.

The court argued that Kik did, in fact, establish a common enterprise when it deposited the funds into a single bank account, using the funds for its operations, which included the construction of the digital ecosystem it promoted.

Both parties filed its respective motions for summary judgment, which went unanswered for six long months. Until September 30, when history was made for legal crypto precedent governing ICOs.

On September 30, 2020, U.S. District Court Judge Alvin Kellerstein ruled in favor of the SEC, holding that Kik’s $100 million ICO violated Howey and thus federal securities law.

Both Kik and the SEC have until October 20, 2020 to submit a joint proposed agreement for injunctive and monetary relief. Kik sold its messaging app business and cut its workforce from over 100 employees to just 19, to raise money to go argue against the SEC in court. Now Whisper owner, MediaLab now runs the Kik messaging app.

Telegram

Back in 2018, messaging app, Telegram launched its ICO, raising close to $1.7 billion from sales of approximately 2.9 billion “Grams” to over 170 private purchases.

The SEC came after Telegram in what could be seen at the time as the highest-level U.S. enforcement action over an ICO, charging the encrypted messaging app with illegally selling digital assets. Specifically, Telegram’s “Grams” are considered to be securities, yet Telegram was offering these tokens without registration statements informing potential investors of the company’s business operations, financial condition, risk factors, among others.

More on the SEC’s recent movements against Telegram can be read at CoinTelegraph.

Rapper T.I. and Coinspark

At the end of September, the SEC alleged that film producer Ryan Felton misappropriated funds and wash traded cryptocurrencies using the proceeds from two ICOS: FLiK, a digital streaming platform, and CoinSpark, a digital asset trading platform.

Pursuant to the complaint, The FLiK ICO raised close to 539 ETH ($164,665) at the time back in September 2018, while CoinSpark’s ICO raised 460 ETH ($282,418) in 2018. As a result, Felton now faces fraud and manipulation charges, according to the SEC.

Specifically, hip-hop rapper, TI and Atlanta residents, Owen Smith, Chance White, and William Spark, Jr. were charged with violating securities law for pretending to be co-owners of the project and recommending investors buy tokens from one or the other of the sales, without disclosing they were paid by the projects.

TI agreed to pay a $75,000 fine and not participate in any digital asset sales for at least five years, according to CoinDesk. Sparks agreed to pay a $25,000 fine and likewise refrain from participating in any securities sales for five years.

DISCLAIMER

Investing in cryptocurrencies and other Initial Coin Offerings ("ICOs") is highly risky and speculative, and this article is not a recommendation by Investopedia or the writer to invest in cryptocurrencies or other ICOs. Since each individual's situation is unique, a qualified professional should always be consulted before making any financial decisions.